The Mechanics of Power is part one of “U.S. Politics: A Brief Guide for Organizers” a three part series from historian and organizer Van Gosse for Organizing Upgrade.

We have lots of “people’s histories” focused on movements, resistance, and protest. They are valuable and inspiring, but they rarely focus on the mechanics of power, meaning the structures of electoral and party politics and the state. If we on the left are going to engage in that kind of politics, we need to educate ourselves to do it right. “Politics ain’t beanbag,” the fictional Irish bartender Martin J. Dooley commented in 1895 — and he was right. If we don’t figure out how it works, outside of the self-serving platitudes of Democratic Party consultants and the journalists who repeat their nostrums, we will have electoral defeat handed to us on a platter.

This essay is an introduction, focusing on basics of electoral politics, and the techniques we need to master to get into the game. Part Two of this series will focus on the peculiar history of the Democratic Party, from its historical roots as the tribune of ordinary white men through its evolution into a broad cross-class bloc linking sectors of capital with parts of the multiracial working class, professional-managerial groups, some women, and LGBTQ communities. Part Three will examine what happens when the “two-party system” begins to break down, and the possibilities for a decisive realignment.

The dialectic of power and protest

The premise of this piece is that it is time to stop just “speaking truth to power”: we need to move towards actually getting some. Let me put it directly: we need to focus laser-like on winning! Have you thought about what winning — gaining a share of governing power, maybe even a lot — would look like? In the past, many of our best organizers assumed that governing was somebody else’s business; some may even have thought it was corrupting. One of the heartening things right now is that more and more of the left is not just talking about challenging structures of power, but taking them over.

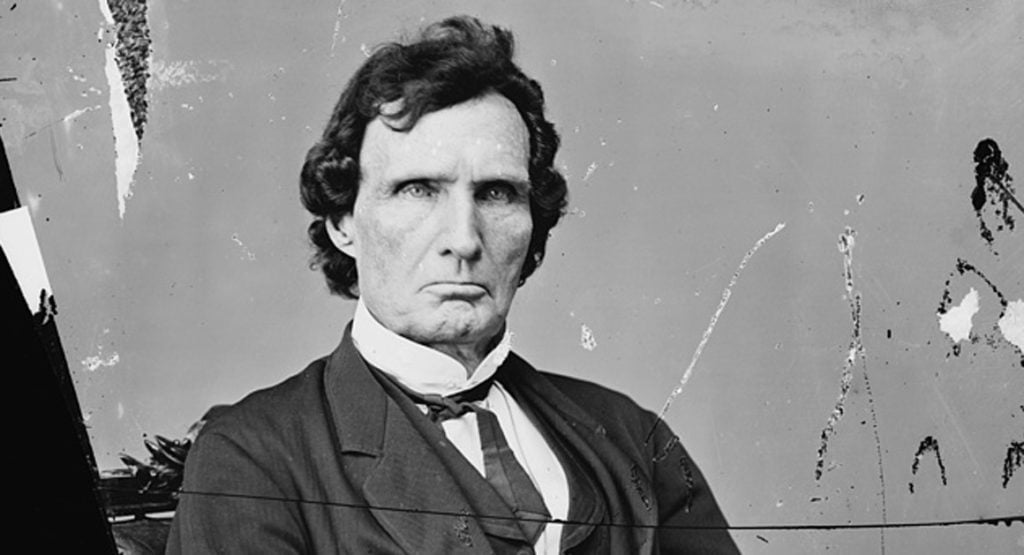

Politics, if we take it seriously, has never been about simply struggling, it is also about governing, and there is a fundamental relation between the two forms of politics. Here the example of the Civil War era’s “scourge of the South” Thaddeus Stevens should be instructive. He was the ultimate Radical Republican, responsible for pushing through the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments which abolished slavery and made the ex-slaves into free citizens. He was also a brutally effective legislative infighter from the 1830s on, feared by his enemies. Stevens knew how to win elections and he took no prisoners. He worked in tandem with the bottom-up pressure organized by militant abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and John Brown, though he is not a well-known name on today’s left like those other three. Because of a radical mass movement pushing party politics to the left, politicians like Stevens were ultimately in a position to change the U.S. state, its Constitution and laws, with permanent effect. You need both, in other words — agitators and legislators; protesters and parliamentarians.

Fifty different electoral systems

Our federalized and localized political system is the most profound legacy of the Constitution enacted in 1789. Because of Article One, Section Four (“The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof”), the U.S. has not one but fifty different electoral systems governed at the state level. Today and throughout all of U.S. history, whether you have a fair chance to vote depends on which state you inhabit on Election Day. Beyond that core fact, the government offices that actually control most aspects of elections are at the county level, meaning there are three thousand different chief election officials whose policies can vary considerably within a given state.

What does this mean for us? To engage in electoral politics, we need to acquire a solid grounding in both the election laws and less-formal practices of administering those laws in your state, county, and municipality. Here are some of the questions we have to answer:

- How and by when must a person register to be eligible to vote in the next election? Does your state have same-day registration?

- What is required to register and what is required on Election Day, e.g. what forms of identification?

- Who is allowed, and what regulations must be followed, to register voters?

- Who is allowed to collect absentee ballots, and how and when will those be counted?

- Do you have “early voting” in your state?

- Where are the polls, and how are their locations used to either guarantee or suppress voting?

- Who is allowed to challenge voters at the polls and how are challenges handled?

- If someone is somehow left off the rolls on Election Day, can s/he vote anyway with a provisional ballot, and how and when will those ballots be counted?

- Who is your county clerk of elections (or the equivalent) and what is his or her record of guaranteeing free and fair elections?

- What legal resources are available to you to challenge voter suppression on or before Election Day?

- And, of course, what offices are up for election (municipal, county, judicial, and state)? Can you say what each of those does? Can you make an effective case for running in each?

These are just a start!

Parties (almost) in name only

Belonging to a party in the U.S. is pretty meaningless. One of the oldest political jokes is attributed to the comedian Will Rogers in the 1930s: “I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.” Think about it: if you register as a Democrat or Republican, what are the practical consequences? You are not required to pay dues, you have no authority to elect your party’s officials (unless you start going to meetings, which may be private and closed). It is a purely nominal membership, except in states with “closed” primaries, where only registered party members may participate.

This is another distinctive feature of U.S. politics. In most countries, it is not state-administered registration that defines partisan membership, but a conscious decision to join an organization, pay dues, and participate in its internal workings. The pretense that people who register as and sometimes vote for a party actually constitute that party has led to a permanent confusion. When people say “the Republicans,” for instance, what or who do they mean? Put it another way: in most countries, you can be expelled from a party, whether you are an ordinary member or an elected official. Not so in the U.S. — anyone who wants to identify themselves as a “Democrat” or “Republican” can do so!

This looseness operates at all levels, and is just as true of elected officials. Consider the following:

Question: “What does it mean to be elected to office as a Republican or a Democrat?”

Answer: “That once you are elected you have made a commitment to vote with others to control the body of which you are a part.”

Throughout our history, the party identity of members of Congress and the state legislatures has been determined by this issue of party control, not consistency in any other respect. We do not live in a parliamentary system, where if a party decides a measure is important, party representatives are required to vote together to back it, whatever their personal preferences — and are kicked out if they don’t. Today the Democratic Party in the House of Representatives equals the caucus who voted to make Nancy Pelosi Speaker in late January 2019, and to elect the Chairs of each committee and subcommittee. Similarly, the Republican Party in the Senate is defined by those Senators who re-elected Mitch McConnell the Majority Leader and other Republicans as Chairs of the various Senate committees. Anything else is for show. Nominally ‘independent’ Senators like Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Angus King of Maine caucus with Democrats and thus functionally are Democrats. If this system were to break down — if Members of Congress started voting as genuine ‘independents,’ forming nonpartisan caucuses to back multiple candidates, as happened in the House Speaker election in 1855 — then you would know existing party alignments really were breaking down.

What holds these parties together?

Gradually, starting in the 1990s and accelerating sharply after Obama’s election, the Republican Party has moved towards operating like a parliamentary party, demanding party-line voting by its elected officials at every level. This kind of discipline is almost unprecedented in U.S. political history. The only comparison is to the Jacksonian Democrats between the 1830s and the 1850s, who usually voted as a bloc on their core issues (pro-slavery and anti-tariff), whether in North or South.

Instead of uniting around ideology and coherent programs, our parties have functioned mainly as coalitions resembling Venn diagrams of class, race, ethnicity, and religion. “Ethnicity” itself has often stood-in for religion, as in the Protestant-Catholic divide that cut through the Northern electorate from the 1830s (when Catholics first became a major group), to the 1950s, when they started defecting from their historic identity as Democrats to the historically Protestant Republicans, because the latter made deliberate appeals to their whiteness.

Even more than religion, however, the most fundamental divide has been regional and racial. Since Lincoln’s election in 1860, there has been a “White Party” in U.S. politics, meaning an organization backed by the overwhelming majority of whites in the former slave states. That regional party used to be called “Democratic” and then switched to being denominated “Republican,” but the party label itself is not that significant. What is different now is that the entire Republican Party, which included substantial numbers of centrists and even progressives into the late twentieth century, has been Southernized, brought into lock-step on a program of white nationalism and laissez-faire capitalism mixed with reactionary gender policies — a real witch’s brew. Conversely, there is currently a big struggle being waged over the fate of the Democratic Party’s Clintonite wing: Will it continue to be a vehicle for corporate control over the Democratic apparatus? Will it be forced to shift its policy mix in order to keep the allegiance of a leftward-moving base? Or can it be subordinated to a rising social justice majority or even be swept altogether aside?

The current polarization and crisis in U.S. politics opens up opportunities to change the electoral landscape overall and the Democratic Party in particular. But to do so we first need to understand the history and social forces that have produced the current Democratic Party, and the structures of that party. So, stay tuned for the next installment in this series!