Earlier this year, Killer Mike made quite a splash with his latest album, R.A.P. Music. Critics couldn’t help but marvel at the unlikely pairing of Mike, with his distinctly southern credentials (and drawl to match), and New York producer EL-P, an underground figure known for his aggressive, frenetic sound. But it was one track in particular, Reagan, that really raised eyebrows. Although Mike’s ostensible target in the song is former Republican President Ronald Reagan (Mike’s not a huge fan – his final line is “I’m glad Reagan dead”) he also takes some unexpected shots at Barack Obama, at one point characterising him as “just another talking head telling lies on teleprompters”. Elsewhere, he compares Obama’s military policies to Reagan’s.

We might be surprised to hear this kind of criticism of the man who, just a few years earlier, was declared “America’s first hip-hop president” because of his deep ties to the genre. Was Killer Mike really attacking the man once dubbed “B-Rock” by Vibe magazine? The real surprise, however, is that the track Reagan is not an isolated rebuke but merely the most recent illustration of the deteriorating relationship between Obama and hip-hop. Killer Mike is just one voice in a growing chorus of dissent from within the rap world by artists who believe Obama has failed to take up the pressing issues facing black people in the US.

“Quite obviously, black America is in terrible crisis,” says Tricia Rose, professor of Africana studies at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “The racial and class dimensions of this crisis have simply been largely sidestepped by the Obama presidency and muted by black leadership, which seems largely frozen by the effect of not wanting to undermine the first black president.”

The waning of the Obama/hip-hop love affair appears to be a two-way street, with Obama showing far less interest in the genre than he did in 2008. In fact, the distinction between his two presidential campaigns is stark.

Rewind to the first election. In the early stages of his campaign, then-senator Obama was making tentative overtures to hip-hop, noting in particular his appreciation of, and interest in, rap music. This was remarkable, in that he was flipping the script on two decades of campaign orthodoxy – followed by Democrats and Republicans alike – that hip-hop was politically radioactive. (In fact, the term “Sister Souljah moment” – used to describe when politicians distance themselves from extreme elements within their own party – has its origins in hip-hop: in 1992, Bill Clinton publicly repudiated rapper and activist Sister Souljah for her provocative comments after the Los Angeles riots.)

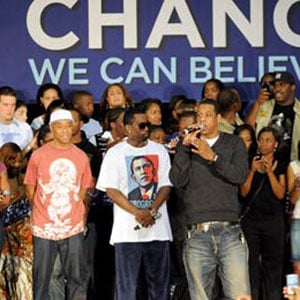

By 2008, seeing the energy his hip-hop affiliations could generate, especially with young voters, Obama was all in – encouraging artists such as Jay-Z and Sean “Diddy” Combs to campaign for him, frequently referencing rap music in his interviews and speeches, and playing rap at his events. In one of the lasting images of the campaign, Obama stood in front of an audience in Raleigh, North Carolina and, invoking Jay-Z’s 2003 track Dirt Off Your Shoulder, pretended to brush dirt off his own shoulder. He received standing applause from the crowd and a huge amount of news coverage afterwards. In that one motion, he had transformed the liability of his relative youth into an asset and, in the process, swept away any doubts that hip-hop would remain front and centre for the remainder of his campaign.

Rappers were more than happy to play their part, too. As early as 2007, Obama’s name started appearing in songs by socially conscious rappers such as Common and Talib Kweli, but it wasn’t until the summer of 2008, when he emerged as the Democratic frontrunner, that Obama sparked a mini-industry of songs and mixtapes making direct reference to his candidacy. A long line of performers – including Nas, Jay-Z, Ludacris, Lil Wayne, Big Boi, Busta Rhymes, Jadakiss, will.i.am, Three 6 Mafia and Young Jeezy – drew on Obama’s rhetoric of hope and change in an effort to mobilise youth and minority voters (and maybe to sell a few albums).

It worked. In the 2008 election, youth voter turnout was the highest it had been in 35 years, and it helped propel Obama to the White House. Fittingly, Jay-Z and Diddy had highly coveted seats on the Capitol steps for the inauguration, while Young Jeezy’s My President could be heard playing from street corners across the nation’s capital. After that, it was clear that hip-hop could be a potent mobilising force. “Hip-hop brought awareness to a group of young adults who probably would not have voted otherwise,” says Jermaine Hall, editor-in-chief of Vibe magazine. “Some were educated on Obama’s political points. Others were just happy to be part of electing a black president into office. Either way the role that Jay-Z, Puff [Diddy] and other hip-hop influencers played in that election can never be denied.”

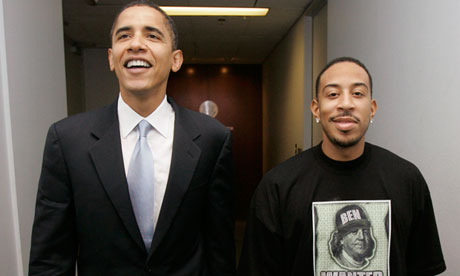

Rapper Ludacris with then Senator Obama after a meeting together in Chicago in 2006. Photograph: Charles Rex Arbogast/Associated Press

Rapper Ludacris with then Senator Obama after a meeting together in Chicago in 2006. Photograph: Charles Rex Arbogast/Associated Press

After the election, however, hip-hop receded into the background. In 2009, the Obamas launched the White House Music Series, which has sponsored a variety of musical performances at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Since its inception, the series has paid tribute to a wide range of genres, including classical, jazz, Motown and country, but rap, the music so instrumental to Obama’s success, still hasn’t been formally recognised. In fairness, the president isn’t entirely to blame for this. In May of 2011, the Obamas invited Common to perform at a White House poetry event, but rightwing pundits – Sarah Palin and Karl Rove foremost among them – doused the event in controversy, using deviously selective readings of Common’s work to argue that Obama had just welcomed an anti-police “thug” into his midst. The story spread like wildfire. It didn’t matter that Common is widely regarded as one of the most positive, peace-loving figures in rap.

The Common debacle is clearly illustrative of the opposition’s strategy. “Republicans have pounced on any and all associations Obama might make with black people in a way that has the potential to turn white centrist and independent voters against him,” says Rose. Fully aware that these voters may see Obama’s rap connections as a liability, Jay-Z noted the need for caution. In a 2009 interview with the Guardian he said: “I didn’t want the association with rappers and gangsta rappers to hinder anything that [Obama] was doing. I came when I was needed; I didn’t make any comments in the press, go too far or put my picture with Obama on MySpace, Twitter, none of that.”

Deciding that potential swing voters are too important to lose in 2012, Obama appears to have capitulated, at least with respect to rap. When his campaign released its 29-song playlist in February, there was not a single rap song on it. There was a healthy dose of country, though, including two songs each by Sugarland and Darius Rucker. Several months later, the campaign expanded its list, finally adding a couple of rap songs, one of which was K’naan’s Wavin’ Flag. This addition was probably less of a tribute to rap, however, than a dig at Mitt Romney. Earlier this year, the Republican challenger used Wavin’ Flag in his own campaign, but was forced to stop after K’naan objected (and then invited Obama to use it instead).

Keeping a safe distance from rap may be a wise strategic move, but putting politics before principle runs counter to the slogan of “change” that Obama ran on, and it has opened him up to some scathing attacks. In his February 2011 song Words I Never Said, Lupe Fiasco raps: “Gaza Strip was getting bombed/ Obama didn’t say shit/ That’s why I ain’t vote for him.” A few months later, the musician intensified his criticism in a video interview with CBS: “To me, the biggest terrorist is Obama in the United States of America.”

Lupe Fiasco has described Obama as ‘the biggest terrorist’. Photograph: Matt Sayles/AP

Lupe Fiasco has described Obama as ‘the biggest terrorist’. Photograph: Matt Sayles/AP

Lupe wasn’t alone. In October of last year, British rapper Lowkey released Obama Nation (Part II), on which M1 of Dead Prez calls Obama “a master of disguise, expert at telling lies”. Using less incendiary rhetoric, the Seattle-based Blue Scholars nevertheless open their song Hussein (Obama’s middle name) with “This ain’t the hope or the change you imagined”, going on to suggest that Obama has failed to address the US’s economic inequality.

Obama is hardly the first political leader to reach power and face a backlash from artists who once supported him, but in the absence of the pro-Obama anthems we heard in 2008 or the deep-throated support of legions of performers, the voices of dissent have become especially pronounced. It doesn’t help that some of Obama’s major fans have changed their tune. Speech, of Arrested Development, who supported Obama in 2008, said earlier this year he was “disillusioned” with the president and would support the Republican Ron Paul instead. Snoop Dogg, another Obama fan in 2008, also seemed to throw some of his support behind Paul when he posted a picture of the politician to his Facebook page with the caption, “Smoke weed every day”, a reference to Paul’s marijuana-friendly platform.

Even those inauguration VIPs Diddy and Jay-Z have tempered their enthusiasm. In early 2011, Diddy told hip-hop magazine the Source, “I love the president like most of us. I just want the president to do better.” Jay-Z also acknowledged problems with Obama’s first term, admitting that some of the criticism directed at the president has been fair. “Numbers don’t lie,” he said last July, during a preview of Watch the Throne, his collaboration with Kanye West. “It’s fucked up out there. Unemployment is still high.”

When asked if he feels disappointed with Obama, rapper Nas expresses his continued support for the president but also his disillusionment with the political process that put him in office. “I’ve been disappointed by politics since the day I was born,” he says. “The historic part of him being elected president was got, and everyone was happy about that, and I’m glad I lived to see it. The flipside is, after we get over that, it’s back to the politics, and it’s something which doesn’t have time for people. It’s its own animal.”

This campaign season in the US has exposed this very tension – for rappers and for Obama. For their part, many rap artists are clearly torn between their allegiance to the first black president and their desire to be straight about conditions on the ground. The Wu-Tang Clan’s track Never Feel This Pain, released last June, offers a lyrical glimpse of this ambivalence. Referring to Obama, Inspectah Deck says: “I never doubted him. I’m proud of him.” However, these lyrics of encouragement are sandwiched between those of frustration. Speaking of his desire for a better life, he says, “I ain’t waitin’ for Obama,” and continues: “Seein’ is believin’, my vision is blurred, ’cause I ain’t seein’ nothin’ I heard, really nothin’ but words.” Album reviews have either read this as criticism or endorsement, but it’s not that simple.

Nor is it for Obama. Facing a struggling economy and a crazy-eyed opposition that has dragged US political discourse to the right, he appears to be striking a centrist tone in order to reach crucial swing voters. This may indeed be the strategy he must follow if he wants a second term, but it’s one that situates him firmly within the very political establishment rappers have long held in contempt.

Erik Nielson is assistant professor of liberal arts at the University of Richmond, USA