“Wen Manong is a phrase used to express respect for an older Filipino man. It is an appropriate phrase to reflect the younger generation’s commitment to remember those who came before them and to learn from the past.”

This quote kicks off the biography Philip Vera Cruz: A Personal History of Filipino Immigrants and the Farmworkers Movement. Philip Vera Cruz was the longest-serving Filipino officer in the United Farm Workers (UFW), acting as vice-president under Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta from 1966 To 1977.

The spirit of Wen Manong runs deep through Filipino-America, especially on the West Coast where the first generation of Filipino immigrants came to work in the fields and canneries, hotels and restaurants of Hawaii, California, Washington and Alaska in the early 1900s.

These manongs laid the foundations for the strong Filipino communities of the American West. They also organized this country’s first farmworkers’ strikes in the sugarcane fields of Hawaii, the asparagus fields of Stockton, and yes – the grape fields of Coachella and Delano, California.

Diego Luna’s new movie about Cesar Chavez was an opportunity to highlight these manongs and the historic alliance between Filipino and Mexican farmworkers. But sadly, the movie falls painfully short of showing our manongs the respect they deserve.

*****

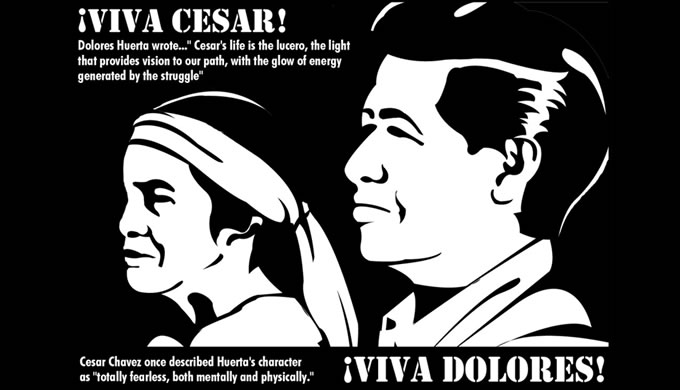

Cesar Chavez, as the charismatic leader of the UFW and gifted organizer behind much of the UFW’s prominence and strategic success, is duly respected through Luna’s movie and rightfully re-centered on the mainstream American stage.

But the story of Cesar Chavez and the UFW is incomplete without a more accurate representation of the Filipino manongs who fought alongside him, co-founded the UFW, and helped win the first contract victory that led to better working conditions for farmworkers in this country.

The problem with Luna’s portrayal of Filipino farmworkers is not that he completely erases their story, it’s that he completely rewrites their story through token appearances and visuals that completely misrepresent Filipinos’ pivotal role.

The movie contains split-second scenes of Filipino workers in the fields and snippets of original footage of Filipinos and Mexicans together on the picket line. There are a handful of appearances of UWC co-founder Larry Itliong — played by actor Darion Basco — but in most of his scenes he just stands at the back of union meetings with his arms crossed for dear life and an intensely confused look on his face.

Some additional nods include the Philippine flag being carried along with the Mexican and US flags on the march from Delano to Sacramento, as well as a large “Filipino Community of Delano” banner as the backdrop to the meeting where Chavez begins his fast for nonviolent resistance.

But overall here’s the story that the movie told me about Filipino farmworkers:

Filipino farmworkers got themselves in over their heads by starting a strike and then inexplicably got penned in like pigs by the growers’ men. Desperate, they sent word to Chavez to ask the Mexican farmworkers to join the strike because they knew they couldn’t save themselves and knew they couldn’t win without them.

Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) step in and save the day by joining the strike. From here on out, the place of Filipino farmworkers is literally in the back of the room, as silent supporters of and beneficiaries of Chavez and his newly formed United Farm Workers (UFW) union. Meanwhile the key non-Mexican players that made the UFW strike and boycott successful were a white lawyer, Bobby Kennedy, and dockworkers in Great Britain who refused to unload cargo ships full of California grapes.

For comparison, here’s the story as I understand it from the point of view of Filipino farmworkers and Filipino-American historians, simplified (but not distorted) to fit a Hollywood screenplay:

Filipino farmworkers or manongs had been organizing in California fields since the 1920s. By the early 1960s, Filipinos made up the majority of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which voted to launch the Delano Grape Strike on September 8, 1965. Though AWOC was part of the AFL-CIO, the manongs’ decision to go on strike was purely their own and made independently of white AFL-CIO leadership. Larry Itliong, a friend of Dolores Huerta’s who would essentially become a co-founder of the UFW, was an organizer with AWOC at the time and was influential in the manongs’ decision to go on strike.

More than 1500 Filipino farmworkers were striking for 8 days before Itliong reached out to Chavez and the NFWA to join the strike. The growers had brought in Mexican workers to cross the picket lines to crush the strike, and in response Itliong, Chavez and other Filipino and Mexican farmworker leaders recognized the need to join forces against the divide and conquer tactics of the growers. Despite very real prejudices and challenges on both sides, Chavez and the NFWA voted to join Itliong and the AWOC farmworkers in the strike. In 1966, AWOC and the NFWA merged to become the UFW with Cesar Chavez as President and Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz and others as vice-presidents. Filipino farmworkers continued to play an important role in the UFW, developing strong camaraderie with Mexican farmworkers and playing leadership roles in the boycott and negotiations that led to the 1970 contract victory that granted workers the better wages, protections and benefits they deserved.

Diego Luna has dismissed this major rewrite of Filipino farmworkers’ role by playing the Hollywood card and saying “it’s movie-making”. At the same time he’s claimed credit for being able to do justice to Filipino farmworkers by “representing a community that hasn’t been represented in cinema, at least the way I believe it should be.”

So which is it Diego? Is your movie just insignificant movie-making, or is it a powerful platform for representation and misrepresentation that actually matters?

*****

The point is that storytelling is never just the harmless act of movie-making, especially when you’ve got a soapbox the size of Hollywood. Storytelling always matters because it is always the powerful act of influencing what people believe about whom and how our behaviors, customs and laws should respond accordingly.

I hope that everyone who tells stories for justice can see the misrepresentation of manong farmworkers in the Cesar Chavez movie as an example of how important it is to respect the stories of allies and collaborators, especially if they are a “minority within a minority”, in the words of Philip Vera Cruz.

Respecting these stories means widening the lens beyond one charismatic leader and beyond one heroic group to focus on the complexity, challenges and triumphs of collaboration. It’s not about going down the rabbit-hole of laundry-listing, it’s about doing the work of giving credit where credit’s due.

Diego Luna’s rewriting of Filipino farmworkers’ roles fails to give manongs the credit they are due. In doing so, he is unintentionally but definitively perpetuating both stereotypes of Asian passivity and conditions of Filipinos’ invisibility and dearth of political power relative to our population in the U.S.

This misrepresentation leaves a void where it should have built a foundation for viewers to ask questions about the fate of the historic alliance between Filipino and Mexican farmworkers, and about conditions for Filipino and Mexican immigrant workers today.

And it hurts all the more because it didn’t have to be this way. Luna could have made some simple changes that would have more accurately portrayed Filipino farmworkers’ important roles. For example, he could have had Larry Itliong front and center at the final signing of the victory contract with the growers, and he could have showed Itliong taking over the facilitation of the meeting at which Chavez declared his fast for non-violence. Both of these true-to-life moments would have gone a long way in showing Itliong for the peer that he was, and in symbolically placing all Filipino manongs in their rightful place in the struggle.

This to me is a very personal example of how those of us who tell stories for justice need to work harder to do no harm in our storytelling. We need to go the extra mile to fill our own knowledge gaps so we can make artful additions to our stories to paint complex but compelling pictures of how movements really work. But for storytelling to achieve this level it takes deliberate intention to do the narrative equivalent of coalition-building. It may be hard and messy just like on the ground coalition-building, but we know it’s necessary to win the respect and dignity that translates into material changes, cultural influence and power for all marginalized communities.